I’m starting to feel burnt out by temples. Or is it that I’m starting to feel burnt out by my early morning starts?

The trip to Banteay Srei started very early because it’s quite a distance from Siem Reap and I want to catch the early morning light on the red sandstone.

It is a cold ride through countryside. It is colder than I am prepared for. In Cambodia, when the countryside wakes up, so do the fires, and the smoke. So fresh country air was beginning to give way to the acrid smoke smells. It feels like we are going fast and the moving air helps.

It’s still dark when I arrive, but within minutes the sun starts to rise, although the sun is not high up enough yet for the sandstone colours to radiate.

Bob, concerned that I am alone, accompanies me to the entrance. This is so unlike my previous tuk tuk driver when I visited Ta Prohm. The walk in there was darker, in a forest and much much further in. Bob tries to light our path with his Nokia mobile phone light and trips. I take out my torchlight instead. I think it embarrasses him a little, he keeps his Nokia phone torch on a little longer, but it’s futile. My torchlight shines like a searchlight.

As we walk in, he tells me that once you could walk into any part of Banteay Srei, but now the middle section is roped off. When we got to the temple proper, we saw roving torchlights in the aforementioned middle section.

It seems that the guards at Banteay Srei like a little side income and via Bob, I was offered the right to climb over ropes for US$3. I turned it down. The bunch of Caucasians wandering in the centre were annoying me. A couple of them were doing yoga poses in the temple. Yeah, it’s a Hindu temple, but this is Cambodia. Don’t be lumping the countries together.

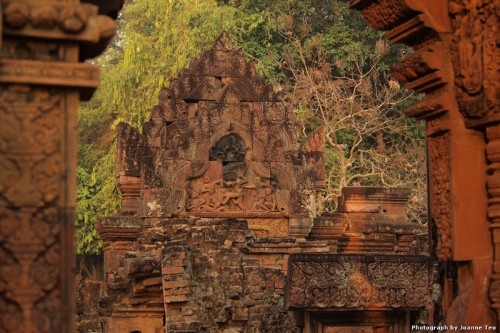

The sun moves further up, or the earth moves further down. Either way, the sun’s rays begin to catch on the red sandstone and the temple glows red. But the group lingers in the roped area, maximising their US$3 bribe. I cannot get a clear shot without people in it. I have to wait and wait and finally they move their bodies out of the way.

I continue snapping away. It’s just the guard and me. And his capitalist instincts get the better of him. He repeats his offer. There is no one around. I bargain him down to US$2. There is no “yes”. There is no “no”. It is a quick look over the shoulder and the lowering of the rope that is the indication of a done deal. I get into the centre where there is no rope. I snap away.

The guard soon gets ansty. Distant voices are heard. More people are coming. He tries to hurry me. I pretend not to understand him. I take my time, but of course I am watching for the crowd. This only works with few people around. Too many people and questions will be asked. Accountability will be required.

I finally leave. I’m offered a new police patch and a plastic police badge that make up part of his worn official uniform for US$5. The same yoga ladies – it turns out they are Americans: “Hell, I’ll take it” – take it. I turn it down. I suspect I can get the same at Psar Leu if I wanted. This is confirmed later by Bob.

Around Banteay Srei, is a conservation park where you can watch birds, take boat rides and so on. It’s quite pretty, but if you want to do birdwatching, you have to go early. I accidentally discovered this and because of my stomping chased a bunch of birds who were catching fish in the lake. It was quite a sight.

From Banteay Srei, we head on through the Kbal Spean which is in the Kulen National Forest.

If you visit the other section of Kulen, you have to pay some sort of entrance fee for tourists for the road maintenence. So I think it’s better to visit Kbal Spean instead, which is included in the Angkor Pass (the same pass used to visit Angkor Wat). And they’ll check for it.

The hike up to the waterfall is not difficult. Indeed, at times it seemed spotless. That’s because there are people actually paid to sweep up leaves. How’s that for job security?

The river bed and banks have carvings – depictions of gods and thousands of lingas. I read that lingams are phallic symbols of Hindu god Shiva. These have all worn down over time, but can clearly still be seen.

From here, we head back toward the direction of Siem Reap to see Preah Khan. Preah Khan is kind of like Ta Prohm, with roots all over the buildings. But the problem with it was that it was packed with tourists. And kids who would call out for sweets in Mandarin for a automatic cheesy smile and photo. The Chinese tourists of course didn’t have sweets on them, so gave them money. As you move further into the temple and away from the crowds, it gets a little more tolerable.

The day before, I’d expressed interest in seeing a more close up view of Cambodian life – you know, the kind that exists beyond the facade of Siem Reap. So Bob made arrangements for me to visit a village. I had a niggling suspicion that he’d use it as a way to earn more money for him, or his family. And so it turned out it wasn’t any village, but a relatives’. And by the end of the night, I was told to give that relative some money. I was already intending to, but it irritated me that Bob felt he needed to tell me.

I might not have understood the language, but for a place that still requires pumping water when you need it, the harsh and hard life, there were a lot of laughs. Either the Cambodians love a good joke, or they just laughed at the end of every sentence.

At the village, Bob and his relatives and the over enthusiastic village kids, came together to catch snails, crabs, shrimp and fish from the padi fields.

To catch a crab, you have to find holes in the mud. You stick a metal prod down the hole. If something catches on, it’s a crab. The hole may go further and to get some indication of what’s inside, you sniff the metal stick. If it smells like crab, you use a spade or cangkul to cut through the mud. But instead of a crab, sometimes you’ll find a snail instead that has taken over the burrow. Or sometimes you’ll find nothing. Either way, you have to pack back the mud and put back what you’ve broken up.

The rule is you can go looking for snails and crabs in anyone’s padi field. But you have to pack back the mud. You can’t just dig and go.

I watched the men wash the catch and hand it to Bob’s wife who cooked dinner in a kitchen on stilts. We ate at another platform sitting on the mat, shoes off, by candlelight. One of the soups contained crab with young green watermelon and pumpkin. It was delicious. The other was a fried mix of the small fish – guts and all – because it’s so small. It was kind of mushy but also tasty. There was also a dish of fermented fish. Bob called this “fish cheese” and it was cooked in egg. It’s an acquired taste. The snails were cooked in a sort of spicy sauce, but they were overcooked so too chewy.

Bob offered me rice wine. I don’t like alcohol of any kind, but to be polite, I took some. As I did with the family in Vietnam. It was vile, but I finished up what I was given.

This is the photo of what was on the eating mat and here’s the rest of the village photos.